Shortly after the outbreak of hostilities, the Royal Navy Corvette Compass Rose is fitted out and commissioned for convoy escort duty. Captain Ericson - the only professional seaman among the officers - greets new arrivals Lockhart and Ferraby, who are quickly put to the test by the brutish 1st Lieutenant Bennett.

Compass Rose leaves harbour for sea trials and three weeks of training for her inexperienced crew. The radar operation training amuses the crew, but a sharp lesson in reality follows when they rehearse depth-charge runs.

Lieutenant Morell joins the crew prior to their receiving active service orders to escort a convoy across the North Atlantic. This proves a baptism of fire, as they are battered by storms and weather the incessant radar search for U-Boats and the unending waterlogging of crew and quarters alike.

As they sail back into their home port of Liverpool, the radio brings news of the slow retreat of the British Expeditionary Force towards Dunkirk. Bennett returns from shore leave drunk and insults the other junior officers. They persuade him to transfer off the ship with a feigned illness, and Lockhart is promoted in his place.

After the port of Brest falls to the Nazis, they encounter their first U-Boat attack. The crew combat efficiently, but two of the convoy's merchant ships are lost. Survivors are taken aboard Compass Rose, where Lockhart tends to them in the absence of a Medical Officer.

The year passes with the enemy growing stronger. Compass Rose returns to port for a re-fit. Chief Petty Officer Tallow takes Chief Engineer Watts home with him and introduces him to his widowed sister, who shares a beer with them both.

Back on Compass Rose, they escort convoys on the Gibraltar run, suffering successive sinkings as they are shadowed by increasing numbers of U-Boats, and filling the decks with survivors. By the time two Royal Navy Destroyers arrive to help, the Corvette is 'full' and the convoy is being pursued by an eleven-strong U-Boat pack - one for every ship left in the convoy. Another sinking sees a U-Boat stop underneath surviving merchant seamen floating in the water, and Ericson decides to steam through them in order to depth-charge the submarine. His anguish at sacrificing British sailors is made all the worse by the lack of success. In Gibraltar, three surviving merchant Captains offer him their thanks and support.

Back at sea, the Compass Rose is forced to stop for noisy repairs, entailling a tense overnight wait. The relief at being underway is soon forgotten as they encounter, but eventually sink, a surfaced U-Boat.

Returning to their home port, they find it bombed and afire. Tallow takes Ward ashore to find his home bombed and his sister killed. Meanwhile, Morell discovers his wife has been unfaithful, and Lockhart breaks off his budding relationship with Wren Julie Hallam, blaming the war.

At night, as Compass Rose heads out, it is attacked and sunk by a U-Boat. Morell, Tallow, and Watts are lost with many of the crew, and Ferraby has a breakdown. Ericson and Lockhart act to keep others alive long enough to be rescued.

Ericson is promoted to Lieutenant Commander and given command of the Frigate Saltash Castle. In a London restaurant, Ericson asks Lockhart to join him as first officer, and Lockhart loyally accepts rather than take a ship of his own. They join the Saltash Castle as it finishes its fitting out.

Escorting a convoy in the Baltic, Saltash Castle encounters a U-Boat, but loses it again after a depth-charge run. Lockhart assumes it is either sunk or escaped, but Ericson is determined not to let it get away. Weakened by the exhaustive search, Ericson approaches the ship's doctor who gives him pills to keep him awake. Suddenly, the radar makes contact with the U-Boat and he returns to the bridge to lead the depth-charge run. Damaged, the U-Boat surfaces and Ericson orders his crew to open fire. After a short battle the U-Boat sinks and its crew abandon ship. The Saltash Castle picks up the surviving German submariners.

After destroying only two submarines, Ericson and Lockhart end their war by sailing past the surrendered Nazi U-Boat fleet.

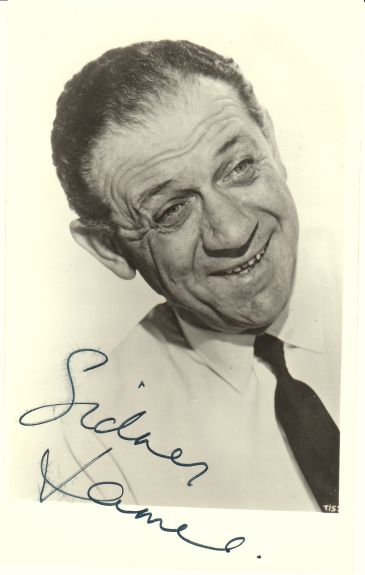

Eight years after the end of World War II, Michael Balcon's Ealing Studios brought Nicholas Monsarrat's best-selling novel The Cruel Sea to the screen, launching the careers of Donald Sinden (Lieutenant Lockhart),Denholm Elliott (Lieutenant Morell), and Virginia McKenna (Wren Hallam), and establishing Jack Hawkins (Captain Ericson) as a star.

Director Charles Frend brought his own experience of the genre gained from The Big Blockade (1941), the acclaimed San Demetrio London(1943) and the spy drama The Foreman Went to France (1942). Frend's documentary leanings (partly learned from working with Alberto Cavalcanti) show through in the raw images of battle and of the industrial nature of the ship.

Co-operation from the Admiralty was extended, though the Royal Navy had either sold or scrapped its fleet of Corvettes at the end of the war, and one had to be brought back from Malta (loaned to the Greek Navy and awaiting breaking). The Coreopsis was quickly transformed into Compass Rose, with the majority of filming taking place on board. Returning to Plymouth one evening, Compass Rose collided with HMS Camperdown, causing considerable damage to the newly fitted-out destroyer.

Scriptwriter Eric Ambler and Frend don't shy away from highlighting the futility of war, and characters express real emotion, rather than a stereotype of repression and control: several officers (including the Captain, Ericson) turn to drink, an officer (Ferraby) has a breakdown, a rating calls the Captain a "Bloody murderer!", and Ericson himself cries when his decision to depth-charge a U-Boat results in the death of British sailors.

This scene was shot several times at the behest of an over-cautious Michael Balcon, who was concerned about the effect on the film such an overt display of emotion would have. It was the original take, with tears streaming down Ericson's face, that was finally used.

Frend emphasises the emotional and psychological damage inflicted by the war, from the callousness of Morell's adulterous wife, to the needless death of Tallow's sister in a German bombing raid. There is a deliberate irony when all those touched by this damage are killed when Compass Rose is sunk in its first enemy attack. This is echoed at the end of the film, when Ericson reflects on only having successfully sunk two enemy U-Boats as they sail past the surrendered (yet still numerous) U-Boat fleet. The palpable sense of futility was seldom seen again in British war films.

MONTHLY FILM BULLETIN

THE BRITISH FILM INSTITUTE

Volume 20, No.232, May 1953, page 65

CRUEL SEA, THE (1952)

The story takes place during the Battle of the Atlantic and is concerned mainly with H.M.S.Compass Rose, a corvette, and her crew led by Lieut. Commander Ericson, the only professional sailor on board. After some preliminary difficulties, the crew settle down and begin to take part in convoy actions. Ericson takes some time to recover from an emotional crisis brought on by his decision to run down some survivors of a sunken ship in order to attack a suspected lurking submarine, but Compass Rose has some success in action later. Lieut. Lockhart finds himself carrying out first aid and realises the horrors of war for the first time. Back on shore, he falls in love with Julie, a Wren from the Operations Room, and Lieut. Morell makes the unpleasant discovery that his actress wife is unfaithful to him. Chief Engineer Watts plans to marry Petty Officer Tallow's sister, but his plans are brought to a tragic end by her death in an air-raid. The Atlantic Battle becomes more intense, and Compass Rose is eventually torpedoed. Many lives are lost, but the survivors are picked up and saved. Ericson and Lockhart find themselves together in the frigate Saltash Castle, this time taking part in the northern convoys to Russia. The war is now making its mark on both men, but they find success in the destruction of a submarine and subsequently pick up the survivors. Home in port again, they realise that a new understanding has sprung up between them.

This notable production, based on the famous novel by Nicholas Monsarrat, has many of the qualities one expects to find in a British film about the sea, and a number of faults common to most war films. The re-creation of wartime life on board the corvette is convincingly built up, and the main action highlights are skilfully shot and tautly edited. The production qualities, indeed, are high throughout, natural sound being effectively used to create moods of tension and tragedy. The central episodes dealing with the torpedoing of Compass Rose and the dreadful plight of the survivors in the open boats, in particular, possess a direct and moving emotional appeal akin to certain British war-time productions. The problem of compressing a 400-page book into two hours of film inevitably involves the telescoping of events and characters which can often prove fatal. In this instance, some of the personal relationships have been altered or softened and the film does not escape being unduly repetitious in its second half; but, although the approach may be an exterior one, this does not invalidate the integrity of purpose which it undoubtedly possesses. The scenes on land, however, especially the romantic entanglements, are handled in a regrettably stiff, over-detached manner which contrasts uncomfortably with the terse, realistic sea episodes.

The capable cast, led by Jack Hawkins and Donald Sinden, includes a number of new faces, and although Ericson is never really built up into a fully realised character, Hawkins' playing is unforced and sympathetic and does not suffer from too much British "understatement". The feeling of gathering strain and the sense of loss of old shipmates is also conveyed by the other characters, who are viewed, on the whole, in a fairly conventional manner. Although it never achieves the extra dimension of a truly personal statement, one is grateful nowadays for a film which does not attempt to depict war as anything but a tragic and bloody experience, and it is this quality which gives the production its final power to move.

The Monthly Film Bulletin was published by the British Film Institute between 1934 and 1991. Initially aimed at distributors and exhibitors as well as filmgoers, it carried reviews and details of all UK film releases. In 1991, the Bulletin was absorbed by Sight and Sound magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment