MONTHLY FILM BULLETIN

THE BRITISH FILM INSTITUTE

Volume 27, No.315, April 1960, page 49

ANGRY SILENCE, THE (1960)

Travers, a political agitator, comes to Martindale's, a factory in Melsham, and forms a works committee with Connolly, a hitherto unobtrusive employee, as mouthpiece. Connolly and Davis, the works' manager, are soon at loggerheads and an unofficial strike is called. Tom Curtis, a young family man, and a dozen others refuse to stop work, but calculated acts of violence quickly bring the others out. When the strike ends, Tom is sent to Coventry and even his lodger and best friend, Joe, ignores him. Travers suggests that Tom should be taught a stiffer lesson. Shortly afterwards, Tom's small son, failing to return home from school, is found by his mother shut in a lavatory, tarred and feathered. Travers now instigates another strike, and again Tom stands firm. This time he is worked over himself and ends up in hospital. On learning that Tom has lost an eye, Joe tracks down the culprit, a Teddy boy, beats him up and drags him back to a works meeting to confront the men with their own shame. Travers quietly leaves town.

The first film of a new production company, The Angry Silence bears striking witness to the effect Room at the Top has had on British cinema. One notes its forthright dialogue, contemporary awareness and air of controversy, its energy and its ambition. Too much ambition, perhaps: the film has several themes - mob law, TUC weakness, bad industrial relations, the right to dissent - whose admixture and thorough working out, possible in a novel, are less ideally suited to the cinema. To cover them all successfully would demand a grasp that is as yet beyond Bryan Forbes', the scriptwriter's, capacities.

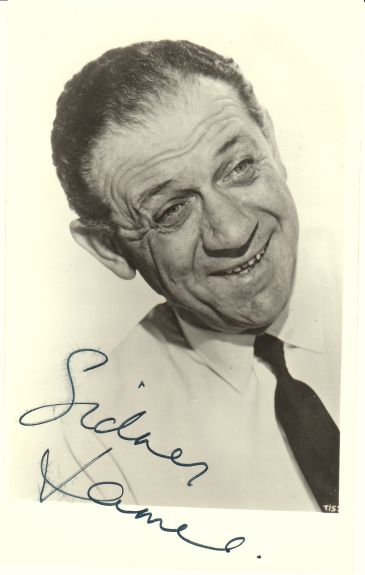

To their credit, the producers, Forbes and Richard Attenborough, have taken evident pains to achieve a surface authenticity. The relationship between Tom and his wife well played by Pier Angeli) is convincing, and some of the incidental detail shows observation - Joe's failed seduction of a factory girl; the bored and utterly fatuous board-room director (Norman Shelley). But as the film proceeds, the hollow schematism of the script grows more apparent. With Tom's battle out in the open, the necessity to give his opponents equal dramatic weight becomes paramount. Yet they remain virtually unidentifiable: shadowy Communist agitator, managing director with an arbitrary mistrust of lone wolves, spineless works committee at the beck and call of a spokesman (Bernard Lee) about whom we, and apparently his fellows, know nothing other than that he is vaguely embittered.

What in fact seems to be emerging is a sort of Fritz Lang study in mob mentality (hero versus fate and a faceless society). It is the last section of the film, however, which most betrays a fundamental weakness in Guy Green's direction. Having already discouraged any attempt to reflect along the way, Green switches from brusque linking shots and shock effects (for instance, Joe is generally identified by a boot on a kick-starter) to the immediacy of arrant emotionalism. From the finding of Tom's son to the pursuit by motor-cycle, the battering of the Teddy boy and the final public expiation at the factory gates, the film's On the Waterfront reminiscences are unmistakable. But a last minute act of double violence cannot compensate for a tangible build-up of cumulative strain, just as the sudden dramatic emergence of four conveniently placed Teddy boys can be no substitute for an investigation into mob psychology - at this stage the film's most highlighted item of unfinished business. One suspects, in fact, that mob rule is the essential subject of the film. But there is really no knowing; neither cogent grasp nor, in the Lang manner, abstract orchestration. Evasiveness wins the day; belief is lost. A matter for genuine regret, because the eye for realism is there.

The Monthly Film Bulletin was published by the British Film Institute between 1934 and 1991. Initially aimed at distributors and exhibitors as well as filmgoers, it carried reviews and details of all UK film releases. In 1991, the Bulletin was absorbed by Sight and Sound magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment